There are some common questions regarding exercise and atrial fibrillation that afib sufferers ask, the ones I hear most often are:

“Did I get atrial fibrillation because of the sport I play?”

“Will my symptoms subside if I stop playing sports?”

“When can I start playing sports again”

“If I exercise more will it help my atrial fibrillation symptoms?”

These questions are all very different, but each one is difficult to answer accurately. This is partly because our knowledge about the connection between physical activity and AF is limited, partly because there are rarely “right” answers to these questions, and partly because each person is so different.

The “U-shaped” connection between exercise and atrial fibrillation

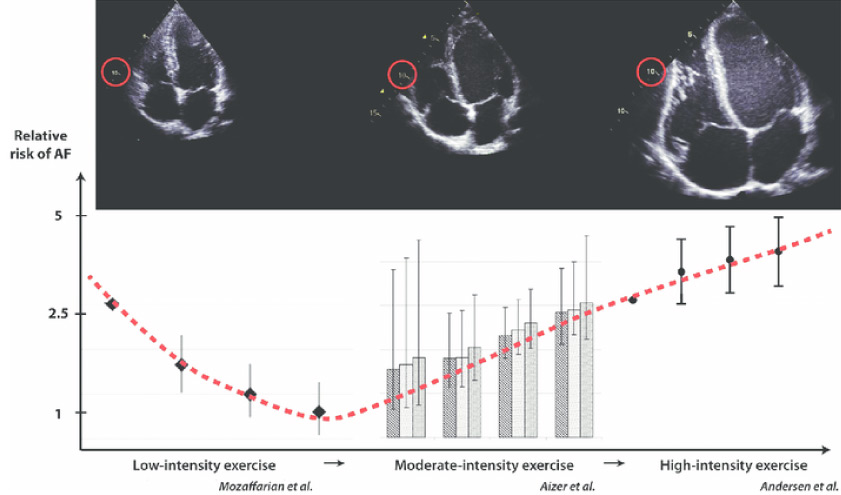

There are many studies that have shown a so-called “U-shaped” connection between the level of sports activity and the risk of atrial fibrillation. “U-shaped” means that there is both a higher risk of atrial fibrillation if you do not engage in any form of physical activity – and if you do a lot of sports. While the smallest incidence of atrial fibrillation is in people who are moderately physically active.

The heart is an incredibly complicated organ. The mechanisms that regulate circulation and the heart vary when comparing inactive individuals with sport enthusiasts. More active people have greater muscle mass around the heart chambers. This is because intense training increases the pressure on the heart as an energy supplier to our other muscles. The heart is forced to work harder and faster, and this makes the heart stronger, just like any other muscle.

The figure illustrates the relationship between the risk of atrial fibrillation and the training intensity over a long period. At the top are ultrasound images of the heart, which illustrate that all the chambers of the heart get bigger the more you exercise. And that the thickness of the heart muscle also increases.

Heartbeat and physical activity

As the heart grows and increases its muscle mass, the autonomic nervous system that controls it also changes. The autonomic nervous system is an automatic system that has both an activating part, called the “sympathetic nervous system” and a resting part, called the “parasympathetic nervous system”. These systems regulate your heartbeat based on your current physical activity.

All of this in itself is an appropriate adaptation to the increased demands on the heart in connection with increased physical activity and an improved physical condition. Unfortunately, this can have unintended consequences if taken too far.

Moderate exercise is key

As heart muscles grow, the atria become bigger. This can lead to an incidence of excess electrical impulses attempting to activate the atria. These impulses, called extrasystoles, are the source of atrial fibrillation. It should be noted that you can experience extrasystoles without having atrial fibrillation, but you cannot get atrial fibrillation without extrasystoles.

The extra beats disrupt the heartbeat between normal heartbeats. As the effect on the resting nervous system is particularly pronounced when we are at rest – and especially when we are asleep – the pulse at rest and during sleep becomes slower and thus the distance between the heartbeats becomes longer.

Since the extra beats can only affect the heart rate between the normal beats, there will be more time for this influence when the heart rate is low. This can be imagined as a stone being thrown to smash a window. The larger the window, the greater chance of breaking the glass. Similarly, as the heart rate decreases, the risk of contracting atrial fibrillation increases.

This means that there is evidence to support a correlation between intense physical activity and the risk of contracting AF. However, it is important to remember that the correlation is far stronger for low levels of physical activities, opposed to high levels.

With this context, let’s take another look at the questions:

“Did I get atrial fibrillation because of the sport I play?”

If you do long-distance running, long-distance rowing, long-distance cross-country skiing or long-distance triathlon, there may be a connection. But not if we are talking about a more moderate – but still relatively intense- level of training. On the contrary, there is less incidence of atrial fibrillation in people who exercise moderately than in people who do not exercise at all.

“Will my symptoms subside if I stop playing sports?”

Studies have shown that moderate physical activity results in both fewer episodes of atrial fibrillation and helps to mitigate the symptoms and impact on the patient’s quality of life. Therefore, you should not stop playing sports.

That being said, you might want to change the type of sport if you currently practice long-distance running. While there are no studies that directly support this, we know that the impact on the heart and nervous system reduces in elite athletes when they switch from an intense training routine, to a more regular training effort.

Ultimately, it is up to the patient to decide what makes sense for them. All physicians can do is provide the information for them to make an informed decision.

“When can I start playing sports again”

I typically recommend starting training after a few weeks, but often this period needs to be longer. In any case, patients should remember that their heart will need to be slowly eased back into exercise. This means that you should start light, and not jump straight back into intense training regimens.

“If I exercise more will it help my atrial fibrillation symptoms?”

There are many studies that show you can reduce the frequency of atrial fibrillation episodes if you improve your physical shape. Especially if you have previously had a low activity level. There is also strong evidence that being in good shape can reduce the discomfort of atrial fibrillation.

As is usually the case with exercise, “too little” is worse than “too much” when we talk about the connection between physical activity and atrial fibrillation. There is compelling evidence that patients gain more from increasing their physical activity, whereas the benefits from lowering it are less.

Conclusion on exercise and atrial fibrillation

From a purely “heart-health point of view”, a high / intensive level of training of five hours per week (ideally with one to two days break per week) will be optimal. More than this can lead to an increased risk of developing atrial fibrillation, and can also contribute to you being more burdened by your already present seizure atrial fibrillation than you would otherwise be. Less than this can certainly also be beneficial.

As the ancient Greek physician and philosopher Hippocrates is quoted as saying 2,500 years ago: “If we could give every individual the right amount of nourishment and physical activity – not too little and not too much – we would have found the safest way to a good health”. Still a wise and insightful statement many hundreds of years later.