Atrial fibrillation may go away on its own or aided by rhythm-regulating medication, but it may also be constantly present, and resistant to medication. If medication have no effect, you can either accept that your atrial fibrillation has become chronic, or stop the flicker with an electric shock.

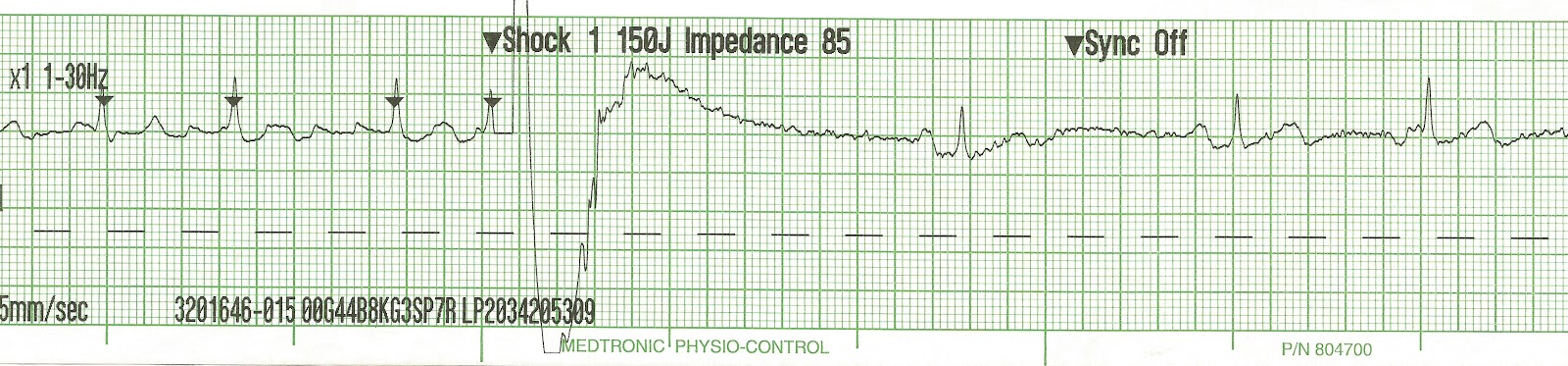

This is called Direct Current Cardioversion or DC conversion. It involves delivering a direct current shock to the chest in an attempt to alter the rhythm of the heart. If successful, this can change the chaotic rhythm caused by atrial fibrillation into a normal (sinus) rhythm.

Anecdotally, it was a Danish doctor, P.C. Abildgaard, who, as early as 1775, described how he first killed a hen with an electric shock – and then brought the hen back to life with another electric shock.

At that time, nobody fully understood the mechanism that allowed Abildgaard to do this. Today, we know that it is important to “time” the shock delivery in relation to the previous heartbeats. Fortunately, the “shocker” automatically takes care of that. This is exactly what separates a dead hen from a living one.

It wasn’t until 1962 that the American physician and researcher Dr. Moe discovered that it was possible to treat atrial fibrillation by administering a shock to a patient’s chest.

By administering a DC electric shock to the chest, doctors can briefly stop a patient’s heart. This is done by extending the resting phase of the heart significantly. Typically, a shock of energy around 150-360 joules in strength is used.

This can “reset” the heart, and cause atrial fibrillation to cease, and the normal impulse formation of the sinus node to take over. This means that the heart resumes a normal heart rhythm, also known as the sinus rhythm.

There are limitations to Direct Current Cardioversion. The shock itself does nothing to prevent atrial fibrillation from returning, whether that takes seconds, weeks, or months. Close to 90% of patients will experience a recurrence of atrial fibrillation within the next one and a half years, even with additional medical treatment to stabilize the heart’s rhythm.

DC conversion is a good treatment option if:

- A patient is very much affected by his atrial fibrillation, and it does not stop by itself or after treatment.

- Medical treatment has started, which physicians believe can stabilize the sinus rhythm.

- It is a patient’s first diagnosis of atrial fibrillation, and the doctor wishes to see if the treatment can cause the heart rate to remain normal, at least for a while.

- A doctor assesses that the patient is urgently better off with sinus rhythm rather than atrial fibrillation.

- The atrial fibrillation diagnosis is associated with temporary stress on the body, such as pneumonia, major surgery, or heart surgery.

- If a patient has had an ablation treatment or heart surgery within the last 2-3 months. During this recovery period, there is a tendency for a heart flicker, which disappears over time.

Is DC conversion dangerous?

There is no evidence that DC cardioversion harms the heart. However, as a result of the DC conversion, there is an increased risk of blood clot complications, including blood clots in the brain, in the first few weeks after treatment, even if the patient is being treated with blood thinners.

This risk may be due to the fact that it takes a few days or weeks before the atria are emptying normally after they have returned to a normal rhythm. This risk is presumably higher the longer that the AF has been present. Other risks include burning of the skin where the shock electrodes have been placed. This is particularly common if the skin contact was not correctly made, or if large amounts of current are needed. Rarely, especially if the contraction of the left heart chamber is reduced, a temporary heart failure may follow DC conversion with a need of (increased) diuretics for a (short) period of time.

Despite these possible complications, DC cardioversion should be considered a low risk procedure.